Protest with dignity, and respond with dignity too

By: Tim Shriver

May 13, 2024

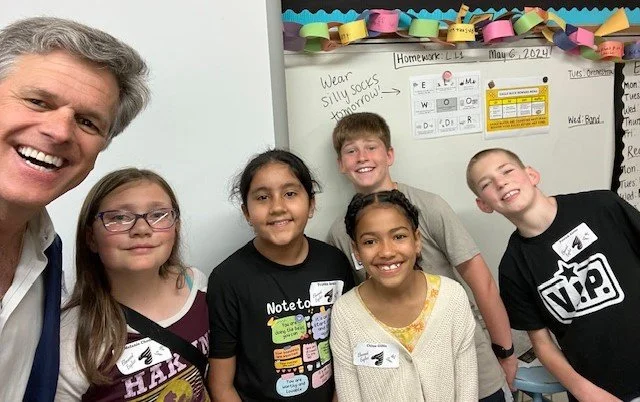

Last week, I visited Elmwood Elementary School in Naperville, Illinois where students, teachers, parents, and administrators are doing amazing work with social and emotional learning strategies and programs. They’ve worked with parents to create a strategy that meets their expectations; worked with teachers to prepare and support them in their classrooms; worked with administrators to ensure that the whole school embodies high expectations and healthy relationships; and worked with students to support their development in all ways. Not surprisingly, they have improving test scores and declining discipline problems to show for it. And a lot of smiling faces, too!

It all came together for me when one student, Patrick, shared his experience. “There’s one word that makes me mad,” he said. “I can’t think of it,” he paused, and then he blurted out, “It’s autism. Autism makes me mad and it makes me sad too. Mad and sad at the same time.” The whole room paused as Patrick looked at the adults. “But it’s okay to be mad and sad. It’s okay to have those feelings. You just can’t throw a chair or hurt anyone else when you’re mad or sad. What I like to do is hug. That’s what makes me feel better. A hug.”

Wow. Here’s an American who gets it, I thought. There’s painful stuff in the world—for him, that’s autism. That stuff creates feelings that aren’t fun: mad and sad feelings. But there are healthy ways to handle those feelings and unhealthy ones, too. Everyone has a right to their feelings but that doesn’t give anyone a right to attack the safety or dignity of others. In Patrick’s case, hugs can be very effective. Patrick learned all that from his family and his SEL teachers and the adults who care about him. Congrats to all of them.

Patrick could teach the rest of us a lesson we desperately need to learn. It’s no secret that there are a lot of mad and sad feelings in our country today and they’re being driven by serious causes. In some cases, those feelings are leading to protests and demonstrations that reflect just how pained and angry the war in the Middle East can make people feel. It shouldn’t surprise us that a violent and terrifying war stokes the strongest of emotional and political reactions. It also shouldn’t surprise us that people expect and even demand that protests are done in a way that is safe and healthy.

A few days ago, a colleague asked if our Dignity Index could offer guidelines for how to “protest with dignity,” and Patrick’s example made me realize we ought to try. The Index is an eight-point scale that ranges from ONE, which expresses total contempt for the other side, to EIGHT, which treats the other side with dignity, no matter what. The purpose is to encourage people to focus on the effects of dignity and contempt and take them into account when making decisions, taking actions, and speaking their minds. It might seem cosmetic, but it’s not. Protecting the dignity of every human being is the only path to a durable peace and ought, therefore, to be a central principal of protest.

Protesting with dignity requires adherence to one basic principle: when expressing a point of view, treat the other with dignity. In our democracy, citizens have the right to express their opinions freely, to appeal to their political leaders for change safely, and to assemble for the purpose of advancing their positions openly. But equally, a democracy depends on citizens doing so without violence against those whose opinions differ. Effective protest depends on treating both authority figures and protesters with dignity.

The Dignity Index does not suggest compromising principles. On the contrary, it invites protesters to state their principles clearly, to promote their positions openly, to advocate for the outcomes they believe in strongly. The Index simply suggests a common principle: express positions and policies while limiting hatred and contempt. Limit your attacks on people in order to optimize your chances of changing policies. Reduce contempt in the way you treat others in order to increase the chances of ending violence and hate.

The Dignity Index is not a tool for compromise or suppression of ideals. Protesters have the right to express their opinions freely and hold authority figures accountable, too. But attacks on the lives or dignity of those with whom protesters disagree has the effect of shifting attention away from accountability and toward personalities. And it has the effect of stifling free speech, too. Treating others with dignity allows for both a clear focus on accountability and an open expression of opinions.

Universities at the center of today’s protests share in these basic principles: treat others with dignity, protect free speech, ensure accountability. They are further charged with advancing the pursuit of knowledge and limiting violence or the promotion of violence against others. The President of the University of Virginia, James Ryan, is one among many leaders who expressed the kind of balance the Dignity Index invites. (See President Ryan’s message here). His actions have been both criticized and supported by opposing interests, but his goals and message remain a strong affirmation of the ideals of protesting with dignity.

From our point of view, the question that will govern the future of the war itself is not whether we feel contempt when we’re deeply wounded, but whether we act on the feeling of contempt, and if so, how? If our contempt is narrowly focused, short-lived, and strategic—meaning that it’s targeted at the direct cause of violence and injustice—it may cause harm, but could also lead to good, so long as it’s balanced in part by dignity. Everyone feels contempt for the other side in a time of war. The question that can determine the length of the war and the chance for peace is the ratio of dignity to contempt.

The fight to defeat the Nazis was fueled by contempt for the evil they did—but much of the contempt was focused on defeating Hitler. Once Hitler was defeated, the allies treated their former enemies with dignity, which has led to 80 years of alliances. The lesson of history is to maximize dignity and minimize contempt, even in matters of war and peace. These principles will determine the course of events in Israel and Palestine, and also here in the United States, where our use of dignity or contempt will determine whether violence there will stir more or less violence here.

If you are talking to those who are convinced that the other side is evil and must be crushed, we recommend listening without interrupting, and then asking: “What do you think might bring the conflict to an end?” If they offer no plan that protects the dignity of both sides, then they have no plan to bring the conflict to an end. If they have no plan to bring the conflict to an end, then how will they defend the people whose lives they want to protect?

I hope that even in these times where there is so much pain and contempt being expressed in our country and around the world, we can continue to create a more safe and healthy culture for future generations. And in that hope, we can cheer for my longtime colleague and worldwide leader of the social and emotional learning field, Dr. Maurice Elias, who’s inviting his campus, Rutgers University, to learn about the Dignity Index. (Read more here.) And we can also cheer for my colleague Tami Pyfer, who gave a brilliant commencement address last week at Utah State University. We can never doubt that our efforts to work together from the bottom up can change the course of history. As the late Margaret Mead noted almost a century ago, it is only small groups of committed people who have ever changed the world.

One very wise fifth grader in Illinois is leading the way on how to act when you’re mad or sad. I, for one, am determined to try to follow his lead.

In peace,

Tim